One of the first things I do when approaching a target is to search for and read through all of their public source code repositories on sites like github.com looking at every file in every directory. I also check through the commit history to see what has changed with each commit. Yes this takes time to do it and it isn’t as fun as jumping straight into hacker typer mode fuzzing inputs on web applications and APIs but it is invaluable. Once I’ve finished the official code repositories of the target I then look at contributors to each of the projects and do the same thing for each of those. Developers often share a lot of code, config, SSH keys, usernames, and passwords between work and personal projects. This has the following benefits:

- OSINT — a huge amount of information can be gained about the target, how they code, their workflow processes, technologies used for the front end, APIs, and out of band processing, URLs called, ports used, etc.

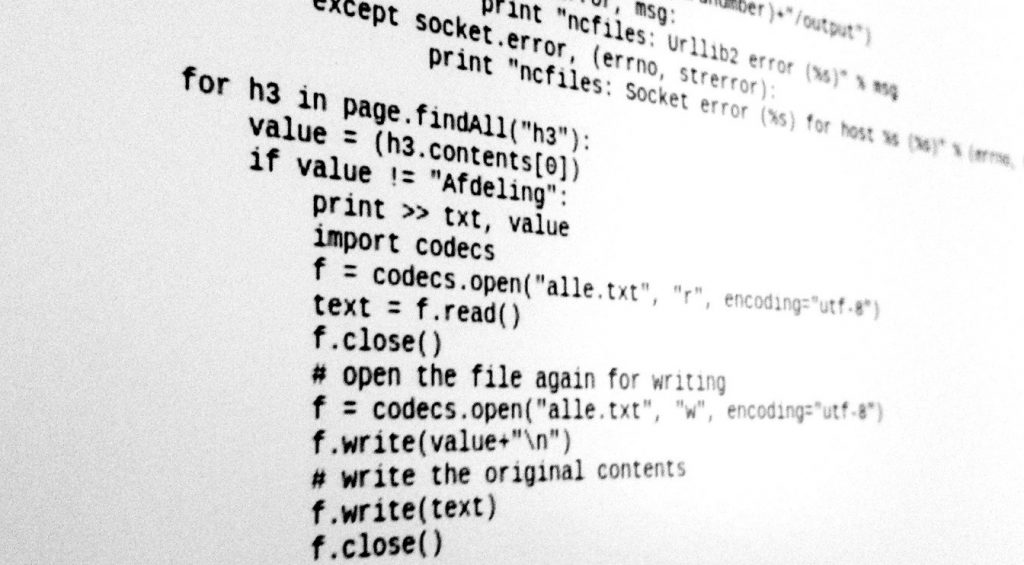

- Understanding — by reading through their application logic you can start to understand how the entire solution works as a whole. If an application uses ruby for their API and python for their post-collection data processing you might be able to target the back end system by slipping crafted payloads passed the front end filters.

- Code analysis — It’s often possible to find security or business logic flaws through the source code that would take hundreds of hours of black box testing to materialise through fuzzing and manual input combinations

- Local tests — it’s always faster to run tests locally than across the network. Also, if you break something it doesn’t matter too much, as long as no external calls are going out to third parties. When testing a production application it’s essential to keep in mind the impact you’re having on their business and customers and rate limiting your testing is a key part of this. Running locally in a sandbox you can go wild. This also removes web application firewalls which allows you to do more without risking your IP getting blocked, which is fixable but annoying. By running locally you can isolate a specific component for your testing and jump back into application states quickly compared to running all of the up-front setup needed for state aware areas of functionality.

- Information leaks — Stored usernames, passwords, keys, domains, URLs and more can find their way into source code repositories. Sometimes they are discovered and then removed, leaving a trace behind in the commit history even though they’re not in the latest version any more. These are easy wins for bounties and an hour or two of reading and searching can often return good returns on time invested in addition to all of the other information stated above.

Reading source code effectively

Speed reading

While I stated above I ready everything I can find, this doesn’t mean I’m slow reading it like a page turning novel. My approach is to skim read each page, getting an understanding of what is going on at a high level while looking for key phrases or patterns that indicate areas of code that I need to spend more time on. When there are twenty different classes defined that do pretty much the same thing I’m looking only for differences after going through the first one.

Prioritisation

It’s important to determine which projects to examine before others. I target projects that have been created from scratch first before moving on to forks from other people as this is where most of the mistakes are made. Configuration files, build files, logs, and non-standard files and directories get my attention first. These provide both context and valuable findings the most frequently. Once these are covered I look at the core of the code to see what’s going on inside. At the same time as this I look through the commit history to track the evolution of the code from first check-in to where it is today.

Next I take a look at the forked projects and repeat the same process, looking for any files that deviate from the origin as the changes are where the vulnerabilities are most likely to exist. Often code gets forked into the target’s account to allow developers to add their own localisation at the repo level rather than doing it at deployment time.

Export everything

Once you start reporting findings to your target those repositories and many others are going to start disappearing pretty fast, even repositories you weren’t reporting against. Nothing bumps a github permissions review faster than a bunch of vulnerability notifications. Make an offline clone of everything you can find but don’t publish them online (that’s just rude)or you’ll be wishing you had done at your first ‘how did that work again?’ moment.

Leave a Reply